Sitka Day 9: Seafood Producers Cooperative

Thanks to the helpful Directors at The Island Institute, on Friday I got to tour the Seafood Producers Cooperative (SPC) fish packing plant. It’s winter, which is prime time for repairs–not harvesting or packaging–but I still got a glimpse of one part of the fishing industry that is the lifeblood of many people living in Southeast Alaska. The hardest thing for a landlubber like me is to wrap my brain around the sheer amount of fish coming through a place like SPC at any given time. For instance, in a few weeks SPC expects a delivery of 35-40 tons of herring. Jeff, assistant plant manager and generous guide, showed me the over-sized tube draped over the docks that’s used to suck the fish up and into the processing plant. “Hold on,” I said. “Did you say tons? Thirty-five to forty tons?” Jeff smiled, nodded. “And that’s a small run,” he said.

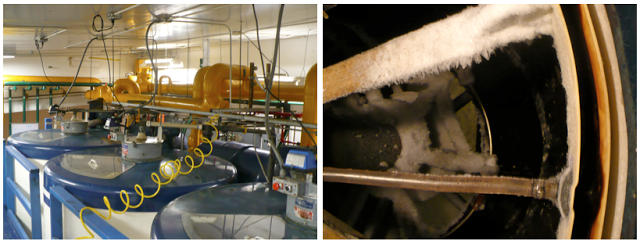

Course the first thing to do after offloading is get those fish on ice. Here’s a glimpse of SPC’s ice machines, which can make 1 ton of ice in 1 hour (the photo shows 3 machines). The perspective is hard to gather from the photo on the right, but a drip tray (right side of photo) gathers water and sends it down the metal spokes and by the time it gets to the bottom it’s frozen and shaved off, then drops below. The ice you see in the background-middle of the photo is actually the bottom of the gigantic machine, some twenty (?) feet below.

A quote from author Joe Upton (Journeys Through the Inside Passage) offers some sense of history with the fishing industry:

“In the mid-1980’s, when it seemed the Japanese would pay any price for herring roe, a lot of money was made here during those few days. At the peak of it, when the price approached $2,000 per ton, some of the hot shots were putting in 25 or 30 tons in a 48-hour opening!…Here, more than any other place in the region, may be seen evidence of the entrepreneurial blood that flows so strongly in the veins of Alaskans. Ruins on the shore are stark evidence of ventures that started, boomed, and finally failed. There were whaling stations, fish meal plants, salmon salteries and canneries, mines, mink farms, and fox farms. Go ashore in any bay; poke around. You’ll find old piling rotting on the beach, rusting equipment hidden by devil’s club thorns, and pieces of someone’s failed dream.”

SPC is on the other end of things, and as a cooperative is able to provide independent fishermen and women with a stake in the business and steadier payment (and lifestyle) over time. Cash buyers (just down the dock here in Sitka) offer other pros and cons, and in the end it’s sort of question of how quickly you need your money and whether or not you’re in it for the long haul or the season (or just a few days, for that matter).

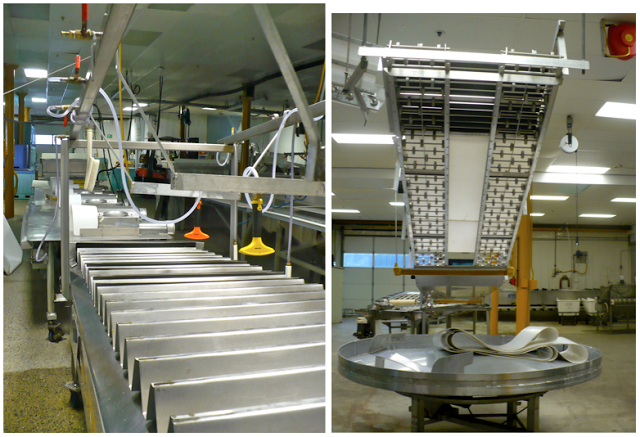

All kinds of fish come through SPC. About 95% of the black cod harvested in these waters and processed at SPC is sold overseas (and probably 70% of that to Japan alone). By contrast, 60-70% of the salmon coming through SPC is sold at home in the United States. Running at full capacity, SPC can process and package up to 100,000 pounds of fish in a single day–and they’re a “smaller” operation. They can move 20 tons of fish per hour off the boats as they roll in, storing them in these huge blue ice bins called totes. If the fish aren’t stored in totes, sometimes they’re coming in off of smaller trollers (trolling is a type of hook and line fishing). The boat pulls in and folks on deck load buckets of fish by hand that get cabled up to the plant where workers can tell by the look, size, color (and probably five gajillion other things I don’t understand) just what species of fish they’re dealing with and how much value it has. Based on this, they sort quickly and send the fish down the line (so to speak). Some fish come whole (“rounds” they call them), while others are gutted or partially prepped on deck. Halibut are huge and come whole. (“You could set up camp in here!” a line worker was said to exclaim upon lifting the side of a gutted halibut and peering inside.) Their first stop is this pneumatic halibut header. Look a bit like a guillotine? That’s because it is.

(At right, that warehouse Jeff is walking to is actually cold storage. An entire freaking building of it. In season, it’s kept at -10 degrees Fahrenheit, if I recall correctly.)

What I can show next is what amounts to several million dollars with of equipment that, together with line workers and the crews that do the catching, produces no small miracle from fish to frozen fillet. Jeff explained how it all works. I don’t dare attempt a replay for fear of total inaccuracy, but take a look and let the mind wander. Pretty soon you’re likely to see fish flopping in all forms, from silvery traces of life to fat, pink, market-ready fillets.

One machine I do remember is the Baader 988, which SPC purchased several years ago. In almost Wilky Wonka Chocolate Factory style, the gutted fish goes in one end and comes out magically filleted on the other. But not just one fish…more like 20 fish per minute are being transformed into computer-perfect, razor-sliced fillets thanks to the Baader, and that’s just the pace for this model, according to Jeff. Lesser quality fish and cuts, and this Baader can fillet fish in under a second. Oh yeah, and it goes without saying: Watch your fingers!

What can I say? The information seems as endless as the industry itself, and this post isn’t even the tip of the iceberg. There’s politics and pressure, lobbying and regulations, pros and cons, good cuts and bad cuts; there’s dog salmon and there’s kings, there’s a “weather-breeder” day that yields a storm that costs a crew thousands of dollars in catch, there’s picture-perfect runs where an entire year’s living can be made a few days…Although it’s dated, I’ve no doubt this quote from Mont Hawthorne (as told by Martha Ferguson Mckeown) in The Trail Led North sums up the lore that, as far as I can tell, still floats in the eyes of Sitka’s fishermen as enticingly as the open ocean itself:

“Whenever a bunch of fellows would get together, someone would start talking about going up North…Things were pretty much settled to the south of us. We didn’t seem to be ready for steady jobs. It was only natural we’d start talking about the North…The fellows who hadn’t been up was hankering to go. The rest of us was hankering to go back.”