A few weeks ago I wrote about mapping place, including

this photo of the homemade map I’m using to navigate my way through writing new essays based on my recent travels. Any good map should tell a story, but the greatest maps also spark the imagination. Ever so slowly, my homemade map has helped me draft an essay that will probably be the introduction to the book, as well as a newer essay based on my travels in Texas. What I haven’t written about yet is my cheat sheet.

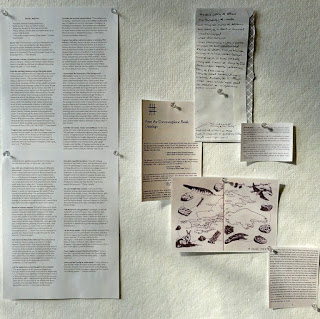

The cheat sheet isn’t really a sheet. It looks more like this (shown at right). Sometimes formally typed up, other times cut out or photocopied, still other times written on scrap paper, this array of notes and occasional images reminds me about the craft tools I have as a nonfiction writer exploring place through the essay form. Sometimes I use my “cheat sheet” as a warm up drill–reviewing it before I begin writing that day. Most of the time, though, I use it when I get stuck.

This afternoon, for instance, as I worked on my Texas essay, I found myself up against a wall. I had just concluded a section about the different meanings of the word “bayou” in the context of Buffalo Bayou in Houston, Texas. I needed this section in the essay because I was working on a metaphor that compared the borderlands of Texas with the “dreaming water” of a bayou. I used Buffalo Bayou as an example because I often went on walks along its shore. But in order to get these two ideas working together toward the next section (about two street vendors outside the county jail), I needed a convincing transition.

When I looked at my cheat sheet, I saw a note I had written about a technique often used by travel writers. By my observations, travel writers sometimes reveal an ulterior motive in the midst of their essays. It’s a good technique that helps turn ordinary, descriptive writing into something with a narrative. Here’s part of the example I used to teach myself this technique, as I observed it in an essay by Ted Genoways, who wrote: “But what drew me to South America wasn’t just the adventure of netting bats. I also wanted a chance to take fuller measure of my father…”

Because any good travel writing is as much about the traveler as it is the tale, I knew whatever ulterior motive I chose for my Texas essay, it had to be something personal. And because “to essay” means “to attempt,” my essays are always an attempt to understand something more clearly for myself. Within a few minutes, I had my transition: “Though I didn’t have to pass the main entrance to Harris

County Jail on my daily walks, I chose to frequently. What drew me there wasn’t

just the borderland. I also wanted to take fuller measure of the street

vendors—two in particular…”

You can see how I quite literally mimicked Genoways’ sentence structure, right down to some of the same words. In a final draft of my essay, that will be replaced by something more wholly my own, but for today’s purposes, the cheat sheet did it’s job. The transition was the glue I needed to get to my next section, and once I had it, I was able to keep writing.