The Writing on the Wall

See? What does it mean? Absolutely nothing and everything, depending on who you ask.

I’ve talked about this before. I’ve praised bulletin boards and I’ve declared the importance of giving something a name. But I haven’t quite put these two things together yet. Perhaps it is because I’ve never worked on such a sustained project like a novel before. I haven’t had to hold this much information in my head, nor have I had to consider “the bigger picture” or “the broader narrative arc” or the “prelonged moral decision” for a large work of fiction. Until now.

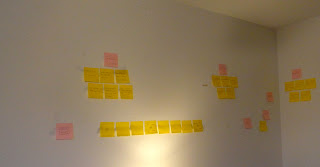

It started with pink Post-It Notes for each main character: Nathan, Tenley, Aaseya, Rahim, and the orphan boy. Likewise, for each main location: Tarin Kowt, Imar, the bazaar, and Western North Carolina. The bright yellow Post-Its I knew I’d need to represent each Humvee in the convoy led by Sergeant Nathan Morris: Reynolds, Sarge, Folson, and Huang riding in the first vehicle; Yak, Caldwell, Mitchell, and Raz in the fifth. All of that was easy. It had been decided months ago and it’s what I call the “surface” of the story–the given facts and structures of the key things in place for the novel.

But I didn’t yet have words for the bigger picture “stuff” I knew needed addressing. So I stared at the wall. A lot. I paced in front of the pink and yellow Post-Its. Back and forth, back and forth. I reread sections of the novel–out loud, to myself, in print, on the screen. All of it once and then all of it again. This part was the hardest. It still is.

After a few days, though, thoughts started to trickle in. First thought: You can do everything right in war and still be wrong. Whoa! That felt true–to me and for the characters in my novel. I wrote it down on a Post-It and slapped it to the desk. Ok. So maybe I thought of something smart. But now I had to do something with it, something that made sense for my characters that were already alive and kicking on page 80 of the novel-in-progress.

Then: You can’t get there from here. That belonged to my character Nathan. I knew it as soon as I heard the words pop into my mind. Then: War doesn’t discriminate, it takes blindly. That belonged to Aaseya, the female Afghan lead character in my novel whose entire family was killed in a misled Taliban attack. Next: He had to have something, anything he could call his own. That sentiment belong to Rahim. No doubt about it.

I wrote all of these down on yellow Post-Its and placed them under the appropriate character. Then I waited. I thought maybe I could think of something else smart. But I couldn’t. Not then.

I did the next day, though.

And the next hour after that.

And by the end of the morning I had a dozen new yellow Post-Its on the wall. I could see, slowly but surely, that each main character in my novel believes certain things–and they have come to believe these things because of the way that war has shaped them (at least up until now, on page 80 of the work). But war is also going to tear those beliefs down. It is going to reveal that even if you do everything “right” in war, you still end up wrong. No matter what these characters believe for their own survival, they are still going to have to face themselves. And isn’t that the truth about life, too? That there’s no escaping ourselves?

Yes. Yes. I believe that sounds like it could be true. Now I just have to turn all that into a damn good story. Easy, right? Only one way to find out…

Engineers work the same way — writing ideas on napkins, envelopes, and so forth — and of course, a white-board on the wall. It foments deep thought to walk and pace, to write while standing, and a white-board is cheaper in the long-run than re-painting the wall every so often. (But there is such a think as black-board paint, which makes a surface suitable for chalk.)

I knew an engineer once who was not satisfied with the limited white-board space; whose inventive diagrams and mathematical scrawlings overflowed onto nearby plate-glass windows, which are perfectly suitable for dry-erase markers.

For us, I think the physical action of moving through space to write helps us to move through the mental space of the problem, looking for the solution. Just be careful if you start connecting things with pins and bits of yarn. Everything looks like a conspiracy then.