#AWP2014 Recap: The Sessions

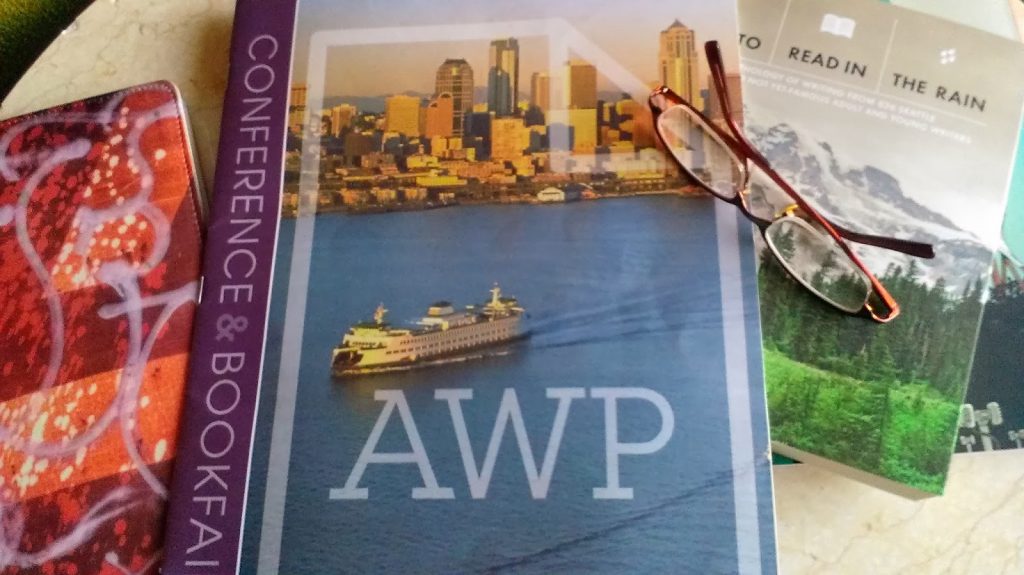

Two weeks of conference and touring: from the 17th floor of a hotel in Seattle to the Kenai Peninsula of Alaska and then some, The Writing Life is back on the blog and ready to re-cap. This is as much for me as for my readers out there because summarizing key points from some of the incredible panels I attended helps me solidify the learning. The conference was packed full with over 10,000 attendees and even held fast as the #1 trend on Twitter after the first day. It was everything AWP always is: thrilling, informative, exhausting, and essential–as well as a reunion with friends and networking with many newly made ones. I can’t cover it all, but here’s the Cliffs Notes from the panels I attended for my own writing’s benefit. I also attended panels to learn about teaching methods and content, but want to prioritize the writing aspects here. Next post, I’ll write about some key encounters with people that I had, including some surprising moments of fulfilling support that got me through some more difficult social moments.

Two weeks of conference and touring: from the 17th floor of a hotel in Seattle to the Kenai Peninsula of Alaska and then some, The Writing Life is back on the blog and ready to re-cap. This is as much for me as for my readers out there because summarizing key points from some of the incredible panels I attended helps me solidify the learning. The conference was packed full with over 10,000 attendees and even held fast as the #1 trend on Twitter after the first day. It was everything AWP always is: thrilling, informative, exhausting, and essential–as well as a reunion with friends and networking with many newly made ones. I can’t cover it all, but here’s the Cliffs Notes from the panels I attended for my own writing’s benefit. I also attended panels to learn about teaching methods and content, but want to prioritize the writing aspects here. Next post, I’ll write about some key encounters with people that I had, including some surprising moments of fulfilling support that got me through some more difficult social moments.

Another Voice in My Mouth: Persona in Poetry & Prose

I most appreciated Virginia Schenk’s assertion that authenticity when writing in persona comes from the details. When I teach flash fiction, I teach that the truth is in the immediate details of our lives and when I wrote Flashes of War, I reminded myself of that daily as I wrote in voices very distant from my own personal experience. Panelist Kathryn Henion shared that, “When we align different perspectives along shared circumstances, we get spectrum and layering, expansion and complexity, that provides more questions than answers. That’s a dynamic experience and we do this to see where the overlaps are, to experiment with empathy, to study change and deconstruction, and to offer a focused practice in persona.” Finally, Deborah Poe said that “empathy has a dual structure of moving towards and moving away,” which I really appreciated hearing because Flashes of War has been called the literature of empathy (a much preferred label than, say, political fiction).

You Can’t Go Home Again: Post-Iraq Assimilation

I most appreciated the insight that war is, generally speaking, pretty far away from our current, American, dominant narrative and that because of this, it’s challenging to create literature that joins that narrative or gets away from it. This gap is only going to widen as we move more toward kill/capture methods and drone strikes, etc. that increase the physical distance between ourselves and the enemy. If anything, new war literature will be literature that addresses this disconnect between reality and the general public’s assumptions. As interesting as that was to hear, half the panelists were missing from this presentation, yet there were five (by my count) other war writers and editors in attendance who easily could have added to the conversation. I wish that a more informal modification had been made in light of the cancellations, so that an organic conversation could have taken place.

Where Witness Meets the Page

I attended this session because I wanted to see author (and presenter) Lorraine Adams at work. She wrote Harbor, among other novels, and I read the first 80 pages of this book in one sitting. She literally swept me away, and as someone who constantly reads writing like a writer and analyzes it, when I find a writer who can carry me swiftly into story, I make a point to read everything they’ve ever written. Lorraine Adams is such a writer, and the panelists at this session were all writing fiction that pays witness to atrocity. Lorraine talked about artistic empathy and dramatizing complexity. She briefly addressed the idea that writing about war from the outsider’s perspective is sometimes impossible–which she, myself, and of course all the other panelists disagreed with. When writing “outside the fog of war,” Lorraine contended, we can often “manage the context and the more complicated ideas at play in the larger sphere with more precision than those who are firsthand witnesses of war.” On this panel, I also appreciated Ru Freeman’s suggestion that “If you don’t have a great love for the people you are writing about, you can’t write a good story about them.” Julie Wu also mentioned the idea of a “seminal moment” as a writer, that is, the moment in which you realized you had to tell the stories you were going to tell. For me, that moment happened in a hotel room off the Atlantic Ocean en route to my cousin’s high school graduation. I wrote “While the Rest of America’s at the Mall” in that hotel room and I knew there was no going back. I simply had to write about these wars and I would do it until I’d come at it from every angle I felt I needed to explore.

Ben Fountain & Amy Tan

I went to hear Ben Fountain read and Amy Tan was, of course, an incredible bonus. Six or seven years ago, I read Ben’s Brief Encounters with Che Guevara, a collection of short stories that’s in my Top 10 of contemporary, American collections. Since then, his novel Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk has received much acclaim and Ben has joined the ranks of us civilian war lit authors adding to the dialogue. I admire his work tremendously. Here are a few quotes I had time to jot down between tears as I was moved by his reading: “The only thing you can control is getting the words on the page. There are so many things you can’t control but that will always be in your favor…You figure out the story by writing it. We go on faith that the story will reveal itself if we’re diligent and the gods are with us…You follow your interest where it leads you. You don’t have a boss, so if you can keep body and soul together and deal with the finances, you’re going to be ok…Writers are desperate people. We need everything we can get our hands on.”

Pacific Northwest Authors on Their Landscape

I attended this session because, obviously, it felt like coming home. Mentor and friend Claire Davis was one of the presenters and she’s the writer I carried with me on my shoulders as I wrote Flashes of War. Her advice came whispered in my ear again and again, and she knows how much that has meant to me, so I wanted to make a point to see her. I really enjoyed her suggestion to consider how comfortable our characters are (or are not) in a given landscape and to ask ourselves, “What is it within the landscape that defines this character becoming an insider?” She also suggested that writers find each character’s central association within a particular landscape feature and then build interaction and metaphor from there.” Kim Barnes was also on this panel and she suggested that writers “think physically about how a particular landscape feature gets into each individual character’s life (ex. sand in a character’s pockets) and into that character’s experience of each scene. How does the landscape manifest? Does it comfort or harass?” Finally, Kim said that “characters do not belong to the landscape until they have experienced loss there.”

Structuring the Novel

Author Tara Conklin suggested that if the structure of your novel draws attention to itself, you need to figure out why and articulate that reason to yourself as a writer. Being aware of this will help you finesse decisions and smooth things out in the long run. She also said that if your narratives are interlocked or interwoven, “know why that is so and how that relates to your personal themes of exploration or interest.” Jenny Shortridge offered a host of structural suggestions, including using a hybrid of the three act play and the hero’s journey structures. Act one is the set up, act two is the seeking, act three is when the character has to engage with the world in a new way, and act four deals with the outcome or the pull away. If you can know where you are within this structure and understand what your character is up to, you can also start to see the holes in your own work. “Most stories are mysteries,” Shortridge reminded, “there’s always something to be revealed.” Look for mood cues, compression opportunities, and emotional mileposts and then deal with the little touches such as rhythm, echoes, and threads that can later become organic organizing features in the novel (ex. my use of the sun in my current novel-in-progress and how various characters’ reaction to it and interaction with it could be written both lyrically and thematically).

Panelist Summer Wood reminded the audience of a Richard Bausch quote: “Every single aspect of constructing a novel is terribly difficult.” She said that in her experience, using counterpoint narratives is powerful because it offers energy that single point of view novels don’t. She quoted Marylinn Robinson’s novel Home, in which a character says that “soul is what you can’t get rid of.” If we can revise our novels with that in mind, keeping only what we can’t get rid of, then the soul will more readily come forth on the page. Ask yourself: “What won’t I let go of? What do I insist on keeping?” and then re-examine the manuscript with that in mind so that you can know your power source and organize the work around that. Once we start paying attention to that deep structure and soul of the story, we can look for connections and build our foundation. Later, we can ask ourselves, “Is my narrative strategy sufficient to my novel’s deep structure?”

Plotting the Realist Novel

First, the panelists spoke to their methods for coming up with plot, which included: thinking in terms of cause and effect in relation to a specific character; seeing what characters do to further complicate their own lives; beginning with a small instigating incident that sets things in motion and gets you to the second act; having a sense of what feeling you want the reader to have and writing your main scenes around that, then dealing with what grows between them; or to pose a question and spend the novel answering it. Second, they discussed handling problems unique to different novels and shared suggestions to: read The Art of Time in Fiction by Joan Silver; consider what individual parts need to be dramatized in the novel and then invent reasons for those parts to interplay and grow; and to be upfront about the issue in your novel immediately and then go from there–don’t make a big secret out of it. Third, the panelists explained what they have learned from their failures: don’t over-tend certain parts of the novel by constantly polishing or re-working them because it calcifies your ability to see other things and move forward or in new directions; make a wrong turn if you must, but plow ahead anyway and don’t be perfect; when your opening premise has gone thin around page 70-100, you need to keep writing anyway; don’t start a book without a sufficient scope; remember that each scene should set up a question and answer a different one and if you get stuck, go back to your overarching question and scope as a motor to propel you forward. Finally, panelists discussed whether plot comes from character or character comes from plot and offered the following insights: plot comes out of the way a character sees the world; look for plot by considering which events allow you to explore the aspects of a particular character that you are most interested in looking at; and, plot creates investment at the beginning of a novel but from there the writer must write to flip that investment to the character.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Subtext

At first, panelists tried to define subtext by describing it as the thing we stumble upon when we trust that our subconscious is a better writer than our conscious mind. One panelist said that “Dialogue is the way in which we say ‘no’ to each other, so if you get to the ‘no’ then your subtext is working.” Subtext is what goes on in spite of the story and yet it often collides at the end of the story by bursting into something even bigger, where images and nouns that we have been building and repeating all along finally lend themselves to something larger and in your (character’s) face. So, how is subtext part of composing a draft? Panelists shared that we need to trust our words and images even if they’re flat at first because they come with a sort of kinesthetic feel and eventually we can move them toward a deeper (and perhaps subconsciously intended) meaning. “Trust your sloppiness,” said one panelist, and then later you can go back and look at those details that seem to hook and see what you can make of them. Another panelist offered: “Deeper meaning cannot be taught; it has to start with the writer actually caring about the characters” and then we can get our heart and our emotional significance and subtext from there; and still another said: “The subconscious is a two-year-old. It will pick up a piece of dirty tinfoil and say ‘Pretty!’ So you have to work with it and find what the right action is to reveal the layer of meaning you want for your particular novel or character.”

How do we do all this? Try writing about characters that thwart your own (the writer’s) intentions and plans for them. Be open to letting your intentions and meanings change from draft to draft. Subtext can therefore be a happy accident that happens when you trust your characters and let go of your authoritarian grip on the plot. If you are a voice-, title-, or image-driven writer (that’s me!), you still need to find the point at which you let your characters take control and respect their privacy and opacity; be patient and know that they will reveal themselves eventually, in tune with the plot and narrative arc. Finally, try looking at your own patterns of imagery and ask yourself where they overlap and how that informs plot. Draw a Venn diagram of this and you’ll likely be amazed at what your images are telling you.